When you read the words “Ramona Quimby,” what do you think of? For me, it’s a rapid-fire slideshow: Ramona squeezing out all the toothpaste in the sink. Ramona with a plate of peas dumped on her head. The fact that her doll was named Chevrolet.

Books have always been like this to me; even when I don’t remember the whole plot, I remember something. I remember the traumatizing fire in Elizabeth A. Lynn’s The Sardonyx Net; Achren’s castle from Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain; the way it felt the first time I read a Kelly Link story; the trees from Midnight Robber. I remember entire scenes from The Lord of the Rings, but then, I read it at least four times as a teen.

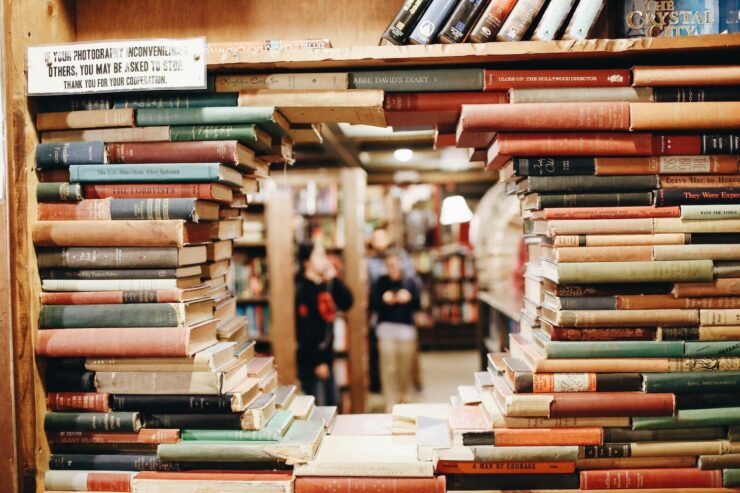

The last couple of years worth of reading, though? I barely remember anything. To say it’s disconcerting is to understate it considerably. Did we read books? Are we sure?

Ages ago, I watched the movie Das Boot with someone who had an extensive knowledge of history. He filled me in on things; he went on tangents, fascinating details I no longer remember because my brain refuses to hold on to historical facts. Like the name of any wine I’ve ever enjoyed, they simply slip in and slip back out again, as if my mental tide reverses itself somehow.

“How do you know all this?” I asked him.

“I don’t know,” he said. “How do you remember the plot of every book you’ve ever read?”

I couldn’t answer, because remembering what I read was something I just did. If you are a book-rememberer, you know this feeling. You know that it’s not exactly useful to remember why Iceland is the place to be at the end of David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks, but that memory is still in there, practically locked away in a vault. A certain reveal in Maggie Stiefvater’s The Raven Boys? Positively etched into my mind. Long stretches from Sabaa Tahir’s An Ember in the Ashes. The cold beach at the start of The Bone Witch. You get the picture.

But pandemic brain fog is real. Stress messes with our brains. When everything is the same, day in and day out, well, that doesn’t help either. As Harvard professor Daniel Schacter put it to the Washington Post, “Distinctiveness improves memory.” In 2020, especially, little felt distinct. There was a Zoom. Another Zoom. Maybe a walk outside, switching sides of the street when someone passed, because there was so much we didn’t know yet. My partner and I took long walks in the hills, ogling expensive houses and catching glimpses of Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens in the distance. But even the trees and the park and the mountains began to blur: A fir tree. A mountain. A sunlit day. (If you’ve had covid, the memory muddle might be even worse.)

Remembering what we read is hardly the most vital thing to remember from these—or any—times. But that doesn’t make the vagueness less disconcerting. I wonder, a little bit, if this is part of why some people have struggled to read at all: if your brain isn’t making the usual memories, even little ones to keep you on the narrative’s path, how do you find joy in a story? Is it just little scenes, strung together by the faintest of recollections?

And, cruelly, the way that some of us throw ourselves into books—gulping down whole tomes in one go—probably isn’t helping, either. That sustained read can be the greatest escape; spending a day blazing through Leviathan Falls is, on the surface, a delightful memory. But two months later, when a friend finished the book and messaged me about it, they referenced parts of it that I could barely contextualize. A study in 2017 found that people who marathoned TV shows retained fewer details than those who watched them week by week. As for books, the same article explains, when you read them all at once, you only keep it in your brain while you’re reading; it’s the need to re-access it that helps you remember it longer.

But, my brain whines, I just want to smother myself in stories as a distraction/treat/escape/way to imagine a different world! Tough titties, brain! We’re going to have to spread things out a little more.

Buy the Book

Spear

“This may be a minor existential drama—and it might simply be resolved with practical application and a renewed sense of studiousness,” Ian Crouch wrote in The New Yorker, in a 2013 piece called “The Curse of Reading and Forgetting.” The problem clearly predates the pandemic, though it might feel particularly acute now. Studiousness? Can we muster up the clarity of mind for true studiousness?

Crouch also says,

How much of reading, then, is just a kind of narcissism—a marker of who you were and what you were thinking when you encountered a text? Perhaps thinking of that book later, a trace of whatever admixture moved you while reading it will spark out of the brain’s dark places.

I don’t know that I can agree that that’s narcissism, not exactly; isn’t that the story of who we are? We are the sum of the people we used to be, including what they were thinking—and reading. We learn when we read, and one of the things we learn is about ourselves: how we react, emotionally or intellectually; what we retain and let go of, where we want to return, where our gaps in knowledge are and what compels us in a story. A book reflects what you bring to it and you reflect what you take away from it. You can’t be who you are without being who you’ve been, and your reading life is part of that.

There are many recommendations for improving one’s memory all over the internet; the experts do what the experts do, telling us to sleep better, eat better, exercise more, go for a walk, look at nature. Touch some grass. Where books are concerned, I tend to think a little more literally: writing down even a few thoughts about each one I read sometimes locks it into my mind a little more, even if it’s just a tweet screaming about how much I loved it. (Writing by hand is supposedly even better for remembering things. Presumably even if you can no longer read your own chicken scratch.)

What did you read last year? What do you remember? What will the things we do—and don’t—remember reading over these years tell us about who we are and what we did?

Last week, for the first time in years, I took a book to a bar. On the patio, on an unseasonably warm day, I laid Matt Bell’s Appleseed open on a picnic table and took a sip of an extremely good drink. Across the way, under the other heater, was another reader.

I’ll remember that one.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.